Coming home to roost: Of migratory birds and reverse migrations

- Aishwarya Mohanty

- Aug 11, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 15, 2025

In the Mangalajodi wetlands of Odisha’s, men migrating for work turn conservationists and guides for birding enthusiasts during tourist season

Aishwarya Mohanty

Sugyan Behera scans the wetlands, trying to spot birds on a monsoon afternoon.

Aishwarya Mohanty/The Migration Story

Mangalajodi, Odisha: The place is Mangalajodi wetlands. The tourist on the wooden rowing boat wanted his boatman and guide, Sugyan Behera, to pluck one of the lovely, purple water lilies blooming across the lake. The 30-year-old Sugyan replied with a question of his own, “Is it very necessary and useful for you? Or would you look at it for some time and throw it?” When the tourist admitted he just wanted to keep the flower for a while, Sugyan gently advised him against plucking it.

“These water lilies attract insects, which are food for the birds. When they decompose, they become natural manure for the wetland and food for other organisms,” he explained.

Sugyan dropped out of school after Class 10, but he knows these birds intimately, their habits, their prey, and their ways, knowledge that comes from years of quiet observation while on the boat.

As he scanned the wetland through his binoculars, pointing out birds and guiding the group of tourists on the boat, he recalled how his deep affection for the wetland, its waters, and the migratory birds grew so strong, it compelled him to return to Mangalajodi, abandoning life as a migrant painter in faraway cities.

Like Sugyan, many others in the village, in Odisha’s Khordha district, have left behind their days as migrants. Today, they are working to build a sustainable future rooted in conservation and knowledge, anchored by a deep bond with the migratory birds that have come to define their very identity.

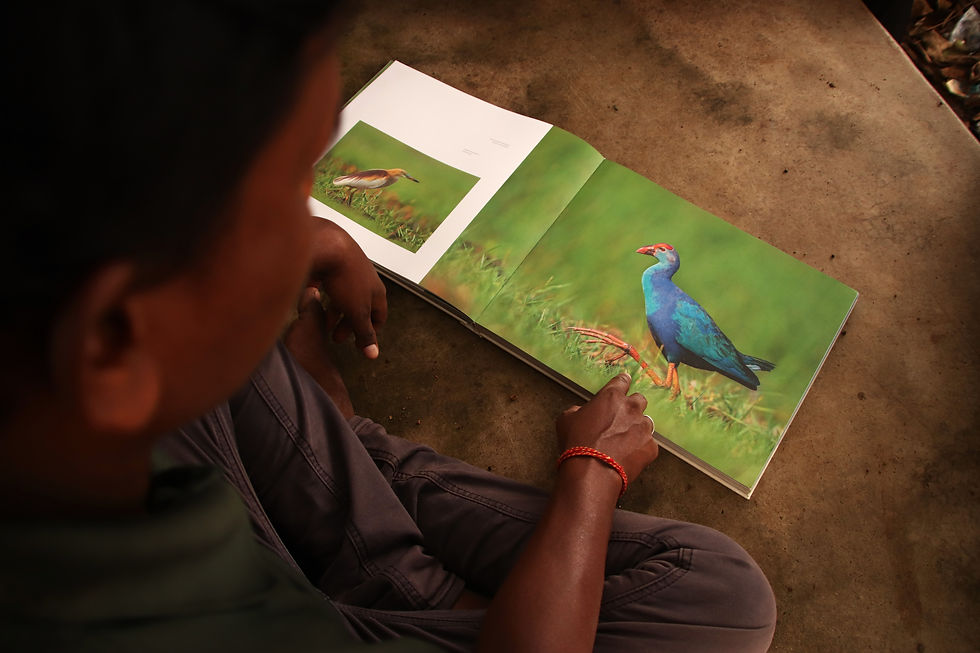

Young avian enthusiasts rely on books and conversations with visiting experts to increase their knowledge of birds. Aishwarya Mohanty/The Migration Story

Making a living off birds

Mangalajodi is spread across nearly 1000 hectares on the northern edge of Chilika lake, one of Odisha’s six Ramsar sites. It was widely known as a village of bird poachers. The birds were consumed, also sold in the market to make an extra rupee.

In 1991, the Chilika Development Authority (CDA) was formed and the restoration of the wetland began.

“When the bird census activities began, it became clear that protecting the wetlands was increasingly vital,” said Dr Sanjib Sarangi, Head, Responsible Tourism Initiative of non-profit Indian Grameen Services, that works on innovative solutions to exigent challenges faced by communities in rural and forested areas of India. In the initial phase, he explained, the CDA introduced incentives for the local community, engaging men to patrol the wetlands, to stop hunting, and to prevent others from hunting.

“However, incentives alone were not sufficient,” Sarangi said.

“What was truly needed was a shift in mindset, a behavioural transformation that fostered coexistence with the wetland ecosystem. The community’s survival is intricately linked to the health of these wetlands; their destruction would have far-reaching impacts, beyond livelihoods alone. We had to help them understand that the birds play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance, which in turn supports better fish catches. Only when this deeper connection was established did people begin transitioning from poachers to protectors,” Sarangi told The Migration Story.

The Manglajodi wetland lies north of the Chilika Lake, Asia’s largest brackish water lagoon.

Picture courtesy Dr Sanjib Sarangi

The transformation happened and has sustained through an entire generation. Starting in the late 1990s, conservation organization Wild Orissa began working closely with former poachers. By December 2000, the Sri Sri Mahavir Pakshi Suraksha Samiti (Bird Protection Committee) was formed, composed, mainly, of ex‑hunters. Over the next several years, guided eco-tourism and alternative livelihoods were introduced, and by the early 2000s villagers were slowly accepting conservation roles.

In the first cadre of these poachers-turned-conservationists was Purna Chandra Behera, Sugyan Behera’s father.

Though Purna and his peers changed course but stayed with the wetland, in the absence of steady job opportunities, their children migrated for work. Eventually, as prospects of tourism-related opportunities grew, the sons came back to take the initiative of their fathers forward.

For a village that called every other bird ‘gendi’ in local parlance, these conservators today know the English and scientific names of the birds and even their unique habits.

“We learned about their behaviour, their appetite, everything, while poaching. We had developed a close association, though for the wrong reasons,” Purna said.

“But now we use the same knowledge for a better purpose,” he adds.

He recollects how they knew that the vivid pink seeds inside the water lily were consumed by birds. To kill the birds, they used to inject a poison—Furadan, which would instantly kill the bird feeding on them.

Now, they conserve the water lilies and its seeds for the birds.

A flock of Indian Cormorants at the Mangalajodi wetland on a monsoon afternoon.

Aishwarya Mohanty/The Migration Story

Call of the wild

Though conservation has opened new livelihood opportunities for many, most families continue to depend on fishing and allied activities, such as fish-vending, net-weaving, constructing boats, for their livelihoods. The declining fish populations, worsened by siltation and upstream pollution, made fishing increasingly difficult. Cyclones are a seasonal feature of the Odisha coastline but after the 1999 super cyclone devastated Odisha, work opportunities shrank further. Migration became the only option.

Fishing and allied fishing activities remains the major source of income for the villagers.

Aishwarya Mohanty/The Migration Story

“When our fathers started protecting the birds, young boys didn’t follow them,” Sugyan said. “They went away to cities like Chennai to earn a living.”

Sugyan himself migrated to Chennai, to work as a painter, after dropping out of school. “Nothing seemed promising here. I only knew fishing and hunting and fish catch was also on a decline,” he said.

But he always missed home. “I wanted to follow my father’s legacy,” he said.

Today, he is back, guiding tourists through narrow channels lined with reeds and lilies, narrating stories about moorhens, bitterns, and grebes, herons, egrets and many others that visit these wetlands from thousands of kilometres away.

Sugyan’s peer, Sanjay Kumar Behera, left in 2002 to work at a CNG station in Gujarat’s Gandhidham. “Most of us left,” Sanjay, 40, said. “There was no land to farm, no work to do.”

In 2013, Sanjay returned to his village. Tourism was slowly, steadily picking up. “By 2015, we saw that tourists were coming to see these birds our fathers once killed,” he said.

Sanjay used to earn between 7,000 to 10,000 Indian rupees while in Gujarat. Now, for every boat ride, guiding the tourists, he charges 1,200 Indian rupees. This is a fixed rate for all boats, applicable in all seasons. The winter months—December, January and February are considered the best season for tourist footfall, and they manage at least two to three rides per day. In other months, as tourist traffic reduces, the boat rides reduce to two to three a month.

“During the off-season, everybody finds some or the other work. Some have small landholdings where they also grow paddy, only one crop a year. Some return to fishing. But some of us remain with tourism-related activities and we do not migrate,” Sanjay said.

Over the years, tourism and the revenue generated from it have seen an upward trend, and so has the curiosity of these young avian guides who decided to stay back in the village while others continued to migrate.

A young guide shows a book documenting the birds that one might sight at the Mangalajodi wetlands.

Aishwarya Mohanty/The Migration Story

Sugyan’s avid curiosity, for instance, has led him to take up eco-guide training. He pored over books like the Bird Atlas and the works of Richard Grimmett. “The learning shouldn’t stop. I listen intently to visiting bird enthusiasts, researchers and scientists, noting down the names of the new species they spot. I stay in touch with them to deepen my knowledge and share anything new that I observe,” he said.

Bhagyadhar Behera, 42, still remembers how, as a child, he was taught to trap birds by his father. “We never understood conservation,” he said. “But things changed. Now, if a tourist wants to see a particular bird, I can take them exactly where it will be.”

The guides follow strict rules: no plastic, mobiles on silent, avoiding bright red clothes that scare away birds. The wetland is crisscrossed with designated boat channels for tourists and specific zones reserved for fishing. Some areas are deliberately left undisturbed so that birds may breed and roost in peace.

In winter nearly 150 species of migratory birds arrive here, flying thousands of kilometres from Siberia, Central Asia and Europe. The wetlands provide them with abundant food: fish, snails, aquatic insects, and native grasses, and a safe roosting site.

“Some birds that were seasonal visitors, like the Glossy Ibis and the Black-winged Stilt, have become permanent residents. We see them here throughout the year, now. These birds are indicators of a healthy ecosystem. They have now made this their home,” said Sugyan.

A purple heron bird with its prey at the Mangalajodi wetland. Aishwarya Mohanty/The Migration Story

A place for all seasons

While tourism has revived livelihoods for some, it is still seasonal. Many young people continue to migrate for work.

Those who stay back want to strengthen what their fathers began. Their dream is to make Mangalajodi a year-round tourist destination rather than one bustling only in winter months, when the migratory birds arrive. They are trying to create livelihood opportunities that engage youth in the village.

“We need a more sustained tourism plan where a person coming here can spend more time even during off-season. This place witnesses so many birds, so many of which have been photographed that the government can support us in developing a bird museum,” Bhagyadhar said.

The opportunities are endless, experts second.

“This village is set amidst picturesque surroundings and has a rich, vibrant culture. There is great potential to develop an eco-tourism plan rooted in a sensitised approach with carrying- capacity-assessment driven self-regulation in tourism management, one that includes nature hikes, food trails, interpretation centre experience, performance arts such as Paika Akhada (martial dance form) and opportunities to engage with the region’s unique socio-cultural and culinary heritage.” Sarangi said.

Edited by Meetu Grover

Aishwarya Mohanty is a freelance journalist and reports on gender, climate change and environment.

Comments