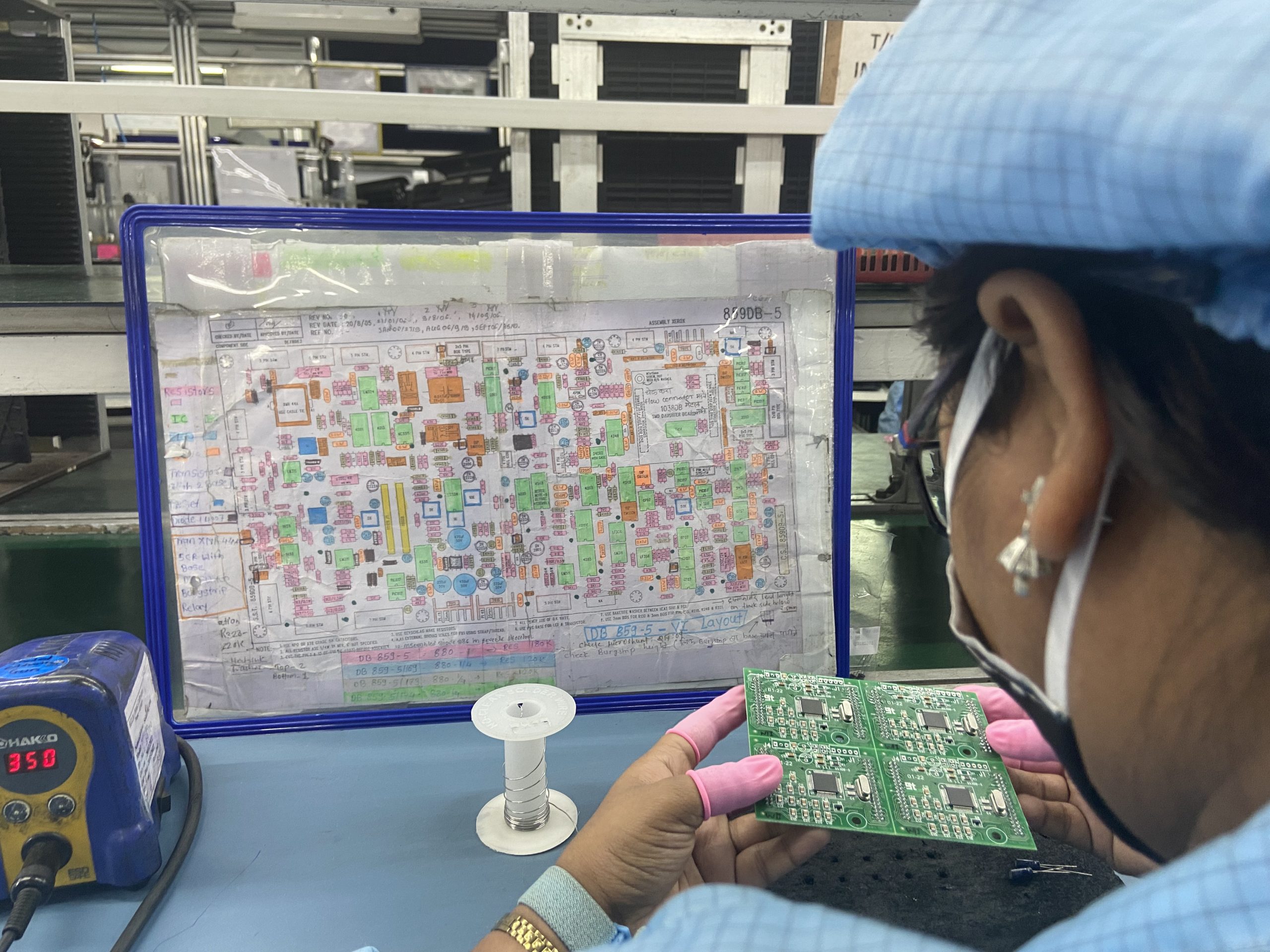

THANE, Maharashtra: When auto mechanic Taterao Gaikwad, 28, received an electric car in his small garage in Thane, he was at a loss. Trained only to fix diesel and petrol vehicles, Gaikwad decided to call his friend, skilled to fix electric vehicles, to identify the problem and repair the vehicle.

“Each time an electric vehicle comes to our garage, I either have to seek help from my friend or ask the customer to take the vehicle to the company. I do not have the skills to fix EVs,” said Gaikwad, working in his garage on a hot May afternoon, as he serviced and repaired a car.

Gaikwad, 28, migrated to Mumbai from Nanded and has studied up to Class 12. He learnt fixing cars at a training school in Mumbai, worked with the school itself for about two years before joining this suburban garage in 2023. Now he aspires to learn more.

“If there is a part-time or a training course with flexible timings available for upskilling, I want to gain knowledge and skills in the EV sector,” said Gaikwad.

The ubiquitous roadside mechanic shops employ hundreds of young men across India, most of them vocationally trained to service, repair and maintain petrol and diesel vehicles. India aims to add more EVs on its roads amid plummeting air quality levels in major Indian cities, but the country faces a glaring skill gap.

Workers like Gaikwad believe the clock is ticking on the transition, and he fears for his livelihood if he doesn’t train soon in electric vehicles.

And not without reason. Pressure is mounting on governments to make the switch to electric, fast.

In January this year, the Bombay High Court sought action to tackle traffic congestion and rise in pollution levels in Mumbai in response to a public interest litigation citing how poor air affects lives, environment and sustainability. The high court stressed that current measures were not enough to curb the rising pollution levels, with vehicular emissions being a major source of Mumbai’s increasingly unbreathable air. The court asked the government to form a committee to study and submit a report in three months if the government can phase out petrol and diesel vehicles.

The Maharashtra government did set up a committee to explore options to cut vehicular congestion and pollution, but informed the court that phasing out petrol and diesel vehicles will have a cascading-effect on people and the country’s economy.

Union minister for road and transport Nitin Gadkari said in an interview with Press Trust of India last year that he wished to transform India into a green economy, and aimed for a future completely free of petrol and diesel vehicles.

The future of work is already becoming all too clear for mechanics like Gaikwad.

“At our garage, only a few EVs come, mostly for painting and denting work. But if there is a technical issue, we need technical knowledge to fix it,” said Gaikwad, adding that 90% of the components in EVs and traditional cars are not the same.

“I won’t lose my livelihood if I gain training in EVs,” said Gaikwad.

THE SWITCH

India approved a scheme last year to spend up to 109 billion rupees to incentivise manufacturers to boost EV production in the country. Sales of electric vehicles in the country touched 19.4 lakh units last year, up from 2.46 lakh units, five years ago.

Like Gaikwad, local garages in Mumbai have seemingly remained unaffected by India’s green push, but the realisation that the transition is not so distant after all is now sinking.

Recent developments in the auto sector have been indicative of what lies ahead.

In Auto Nagar in Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh, thousands of workers became unemployed and had to shift to other sectors unable to fix vehicles compliant with Bharat Stage – VI emission standards, according to a report in The Hindu. Many traditionally skilled workers said they were ill-equipped to repair these vehicles.

“The biggest challenge lies in labour transition,” said Abhishek Sinha, founder of WeBeliev, a Singapore-based consultancy firm that works on sustainable businesses, and podcast host of ‘The EV Equation’.

“The shift to EVs could benefit informal workers like repair labourers, ride-hailing drivers, and the small and medium enterprises. We shouldn’t—and can’t afford to—lose this workforce,” Sinha said.

For now, the transition appears distant to local garage technicians since most EVs are new and still under the warranty period so they go to the companies for repair and upkeep. Like Gaikwad, other mechanics too said they had found a temporary solution to fix them, from relying on a friend who is skilled to work on EVs, to learning about EVs informally or from peers, and also exploring YouTube for tutorials.

They acknowledged that with the growing pollution and the government working to cut carbon emissions, “change is inevitable”.

“We receive one to two EVs to fix brakes and for cleaning. Electric cars are new, and their features, performance, especially during the rainy season, are still underexplored,” said Mayu Mayya, who runs Mayya’s car studio on Thane-Ghodbunder road, where all kinds of cars, from affordable to high-end cars, come for servicing.

“Electric cars are still facing problems with the distance of travel and charging infrastructure. The problem is pollution, and irrespective of one’s choice, EVs will come,” he said.

THE AIR WE BREATHE

At 13%, road transport is one of the biggest contributors to the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Of the world’s 100 most polluted cities, 39 are in India, according to the S&P Global Mobility, a division of S&P Global, which delivers data, forecasts, and analysis on the automotive and mobility sectors.

As part of its ongoing efforts to cut emissions, India has set an aim for 30% of its vehicular fleet to be electric by 2030. The country offers various incentives and policies to encourage EV manufacturing. India produced 1,681,030 units of EVs last year, up from 174,500 units of EVs five years ago.

Many are making the switch to electric to cut expenditure on fuel and often as a conscientious choice to protect the environment.

Ramesh Manohar Paraskar, 73, a retired railway employee, bought an electric scooter last year, finding it easy, affordable and a non-polluting drive. But he struggled to get it serviced from local mechanics.

“I had to take it once when the scooter’s brakes had an issue, but they clearly refused because they lacked the skills,” Paraskar said, who earlier owned a car and said he could get it fixed from any local garage.

“Now, I have to book an appointment in the nearby service centres for its upkeep and maintenance,” he said.

GROWING DEMAND

The global demand for green talent grew twice as quickly as supply between 2023 and 2024—with demand increasing by 11.6% and supply by 5.6%, according to the business-focused social network LinkedIn’s Global Green Skills Report 2024.

The report predicted that by 2030, “one in five jobs will lack the green talent to fill it” and by 2050, “this gap will balloon to one in two jobs”.

While India offers skilling courses for EV repairs and maintenance, these programmes often suffer from poor interest from the youth.

A skilled workforce is needed for EV components as well. India’s automotive industry will require 200,000 skilled people, with 30,000 EV-ready workers every year till 2030 to achieve the government’s vision of 100% localization of EV components, according to a Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers study.

Mehraj Khan, a migrant from Uttar Pradesh in Mumbai has spent 15 years in the auto sector and currently works as a service advisor to technicians and wonders if there are courses he could join.

“I used to work as a mechanic in UP, and later came to Thane with my friends for better employment opportunities. Currently, I have limited knowledge about EVs, but I am eager to learn about them either through government training centres or at my workplace,” said Khan.

This informal skilling route that auto mechanics are taking is worrisome, said transition experts.

“If YouTube is the learning platform, companies must make quality training videos in regional languages and team up with influencers. The main challenge is workers don’t yet see the value in upskilling because EV use is low (5%). But EV repairs have higher profit margins, and once workers know this, their interest in learning will grow,” said Abhishek Sinha, founder of Singapore-based WeBeliev, a sustainable business consultancy, and podcast host of ‘The EV Equation’.

The Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers’ study highlighted that 43% of the technical skills between an Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and an Electric Vehicle (EV) had minimal overlap, requiring newly upskilled talent. There is also the need to re-skill the existing workforce.

The Indian government and the auto industry expect the creation of 60 million direct and indirect jobs in the EV space (calculated on a demand projection of 102 million units by 2030) – from manufacturing to services, technology for battery to charging infrastructure.

While state and centre policies are assuring creation of jobs within the EV industry, the pace is slow and the supply to the workforce is insufficient to meet demand.

“Government programs, not just for EVs, often struggle with outreach. Messages about upskilling opportunities rarely reach workers. Many aren’t aware such (skilling) centers exist. The government or CSOs need to step up communication—using WhatsApp, posters, or local channels—to direct workers to these opportunities,” stated Sinha.

He further added India already has a strong skill development infrastructure. The need now is to link it with industry—bring in companies like Tata or JSW to partner with ITIs or engineering colleges for targeted EV skills like battery or electrolyte management. Second-tier colleges and sustainable hubs can also play a crucial role in training the blue-collar workforce.

Besides, reskilling and upskilling must be a core part of India’s EV transition—not just an add-on, said Siddharth Sreenivas, head of Transport and Mobility at Asar—fosters sustainable social and environmental change through research and collaborative partnerships. He said affected workers should be identified and supported meaningfully.

“Skilling can’t be an additional aspect to it (EV transition). It has to be a more integral part of the whole transition,” he said.

Mansi Bhaktwani is a correspondent with The Migration Story