Recent estimates from the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM) suggest that over 400 million (EAC-PM, 2024) people in India have migrated internally, from both rural and urban areas. While the report does not provide a rural-urban split, the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2020-21 estimates that 26.5% (GOI, 2021) of rural and 34.9% of urban populations are migrants.

For millions, however, migration is not about choice; it is about survival.

Nearly 65% (PIB, 2023) of India’s population depends on agriculture, making livelihoods highly vulnerable to monsoon variability. Over half (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2022) of India’s farmland is rainfed, so a single bad season can devastate families. This year alone, erratic rains damaged over 2 million hectares (Indian Express, 2025) of farmland in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Himachal Pradesh, and Telangana, resulting in losses of thousands of crores. For small and marginal farmers, such shocks often trigger a painful decision, whether to stay and starve or to move and survive.

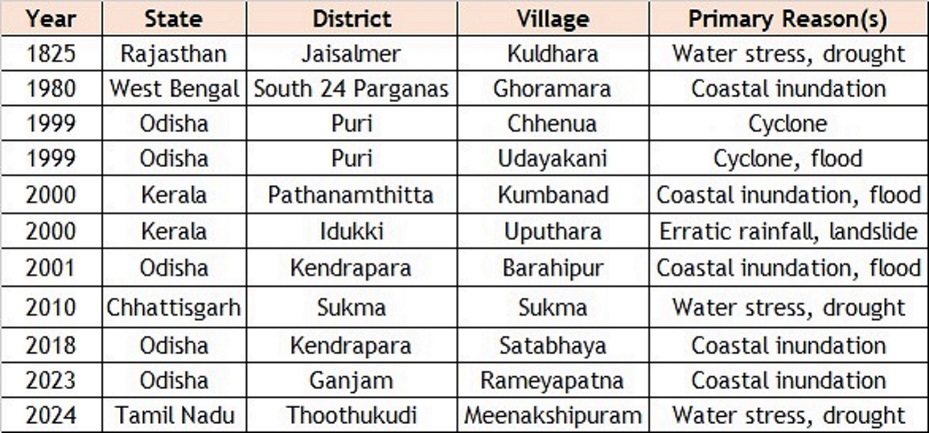

Climate stressors such as droughts and floods push farmers and farm laborers to migrate in search of alternative livelihoods. Between 2008 and 2023, more than 56 million (Statista, 2024) people were internally displaced by climate-related disasters. Numerous villages have been abandoned (Mohraj et al., 2025) over the years due to such events (Table 1), underscoring that migration is often a response to climate uncertainty rather than mere economic aspiration.

While the uncertainty of climate still persists and will continue, communities are finding ways to adapt.

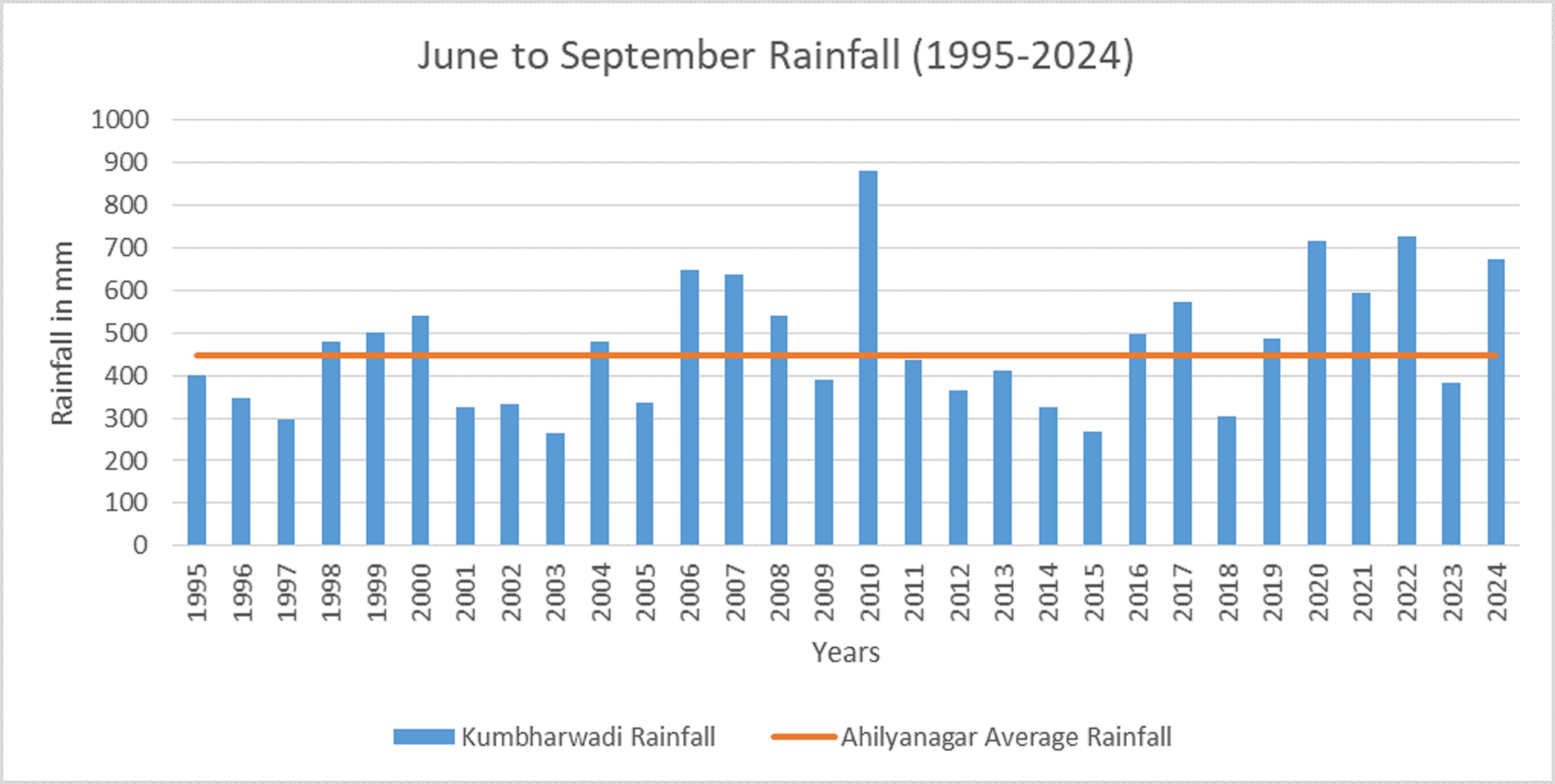

Kumbharwadi village in the Sangamner block of Ahilyanagar district, Maharashtra, is known for erratic rainfall.

From 1995 to 2024, Kumbhawadi received rainfall below Ahilyanagar’s June-September average of 448 mm in 15 out of 30 years, making the village prone to drought (Graph 1). The farmers majorly cultivated pearl millet during the monsoon season, and a few handful of farmers produced sorghum during the winter season due to limited availability of water resulting in poverty. In 1998 (WRI, 2013), half the land was deemed unproductive, forcing families to migrate for 6-7 months each year, creating a situation of hardship.

To improve the situation, a watershed development project covering 910 hectares was initiated through the Indo-German Watershed Development Programme (IGWDP), by Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR).

When it rains, water flows from hills and slopes flowing from a few hectares of area to thousands of hectares creating multiple streams. These streams converge at a point to create larger streams which eventually drain into rivers. Managing this natural flow of water and the land that channels this is called watershed management. This process is crucial because it reduces the surface water run-off and soil erosion, improves the groundwater recharge and ensures the sustainable water availability for agriculture and local communities.

The process of initiating watershed development involved villagers willing to be associated with the project by signing an agreement that included a ban on tree cutting and free grazing, along with community contributions. Over the next four years, the community, working with developmental organisations, undertook watershed development projects in different phases. The initial 18 months focused on building villagers’ capacity for various soil and water conservation measures. The village development committees were entrusted with planning, implementation, and record-keeping in accordance with the WOTR.

In the second phase of watershed development, the community, along with the WOTR, prepared a feasibility report using a participatory net planning approach that identified the most suitable watershed activity to maximize returns. Activities like farm bunding — a process of creating small barriers at the edges of the hills/slope to prevent water from flowing too quickly was done on 492 hectares, and tree planting and contour trenching– a process of digging shallow ditches along the natural slope to slow down the rainwater which helps in water to percolate and reduce run-off was done along 375 hectares.

The results were transformative: soil erosion was significantly reduced, resulting in increased green cover, which was quite visible when we visited the village. Furthermore, with increased water availability from better water management practices, non-monsoon cultivation increased by over 60%. This allowed farmers to shift towards cash crops like tomatoes and onions, along with groundnut, chickpea, and green gram, resulting in an increase in the income of the farmers.

The reliance on water tankers also decreased significantly, from 60 in 1998 to only a few during low rainfall years. Farmers not only diversified into cash crops but also shifted to natural farming using Farm Yield Manures (FMY) and bio-pesticides, bio-gas plants, and livestock rearing. These initiatives diversified the climate risk for farmers, so in the event of any climate uncertainty, crops fail, the farmers have continued support from livestock to sustain their income. Kumbhrwadi village now has three milk collection units, paying farmers 40 rupees per litre, providing a steady income and a backup against agricultural uncertainty.

The village’s situation went from a plight to prosperity and continued to yield returns even after 25 years. We spoke to Ramesh Ramnath Hondare, a villager from Kumbharwadi, about the situation before the watershed development and the current situation. Hondare said, “Earlier, when there was less rainfall, we used to migrate to neighbouring villages to work as agricultural labourers. Over the years, I started cattle rearing, along with poultry and goat rearing. Initially, I had only desi (local) cows, but now I have crossbred cows for better milk production. Earlier, our village had just one dairy, and today we have three. From milk alone, I earn around 2–3 lakh rupees annually, and from goats around 15,000–20,000 rupees. Things have changed. Earlier we used to migrate for work, but now we are able to sustain ourselves here in the village”

The improvement in cropland value resulting from continued management of commons by village development committees has enhanced resilience, leading to almost no farmers migrating for work.

Just a few kilometers away, Mahandulwadi village in Shrigonda block in Ahilynagar tells another story of change. Until recently, non-farmland owners survived by breaking stones and travelling far distances under scorching heat. “Most people in our community do not own farmland,” said Meera Mahandule, a livestock enterprise owner and a part of the papadum group enterprise. In India, non-farm owners either work as agricultural laborers or migrate for work, depending on the season and the availability of work. Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) are the second-largest employment-generating industry, with a high prevalence in rural India, yet they face challenges such as high input costs, lower productivity, and increased price competitiveness. Moreover, these enterprises in rural India still face infrastructure challenges (Prakash et al., 2021) such as power, communication services, storage facilities, and roads, along with inadequate marketing and business skills, access to credit facilities, and financial discipline.

To bring rural women into the entrepreneurial step-up, a group-based savings and credit management program was initiated in Mahandulwadi village in Ahilyanagar district. The initiative focused on building enterprises such as livestock rearing, tailoring shops, onion processing units, kirana stores, and paper plate and papadum-making units. The idea of starting an enterprise raised several challenges within the family of these women. With many women not completing their education even till grade 10, it was difficult for the developmental organizations to build confidence and trust in the community due to perceptions and fears of scams and fraud. Convincing their husbands and family members was also a challenge for the women entrepreneurs, but with the organization’s persistent efforts, they were able to initiate an enterprise, becoming the first-generation women small enterprise owners. The women entrepreneurs were trained by experts on business development, finance and usage of technology along with exposure visits to different MSME’s to bring a broader understanding of the business environment.

Meera points out, “We used to work as stone breakers for daily wages. Our livelihood was so vulnerable that we would not have had a meal at home if we didn’t work that day. We used to be late returning from work in the evening and often our children would go to sleep waiting for us without eating anything. We worked in high temperatures, and getting wounds on our hands and legs from breaking stones was a daily occurrence for us. However, since joining this project, we’ve been able to leave that arduous work behind”.

Due to these interventions, women like Meena from Mahadulwadi no longer have to leave their families in search of work, they themselves can now provide for their families and have regained dignity in the community.

India’s internal migration now reflects not only economic dynamism but also changing socio-ecological realities, and this comes at a cost. From broken community ties to lost cultural connections, and emotional distress. The key to reducing rural migration is not only economic development but sustained, community-led adaptation. Schemes (Ministry of Rural Development, 2021) like the Watershed Development Component-Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (WDC-PMKSY), launched by the Government of India from 2021 to 2026, with a target of reaching 4.95 million hectares and a total financial outlay of Rs 8134 crore, can create transformative change in rural India. Along with agricultural improvement, there is significant potential for improvement in India’s rural MSME sector. Credit access for MSMEs has increased (Niti Ayog, 2025) from 14% to 20% over the last 4 years, yet a substantial gap remains. To fill this gap, there is a need for tailor-made policies that improve rural communities’ access to infrastructure, capital, and training.

As global dynamics continue to change, empowering rural communities to adapt sustainably is crucial. Real freedom lies not in moving to survive, but in having the means to stay home with dignity.

Faraz Rupani is an economist at the WOTR Centre for Resilience Studies (W-ReS), focusing on sustainable development, climate finance, rural resilience, and climate change.

Pavan Khadse is a researcher at the WOTR Centre for Resilience Studies (W-CReS) and a social development professional specialising in CSR projects’ Monitoring & Evaluation, and community-driven development.